Scientists recently created the first “synthetic” embryo to develop a brain and beating heart.

What differentiates synthetic embryos from those created via IVF is that these so-called embryo “models” are produced asexually — without eggs or sperm. Researchers applied chemicals to pluripotent stem cells to encourage them to develop into the types of cells that form embryos. Coaxing these cells together, scientists observed that a small minority of them subsequently self-assembled as they are programmed to do, into embryos with brains and beating hearts.

While these experiments have only been carried out in mice thus far, researchers indicate they have plans to proceed with a similar experiment using human cells. “This is providing an ethical and technical alternative to the use of embryos,” claims Professor Jacob Hanna, leader of the team that published the study in Cell.

And while research on synthetic embryos could potentially alter the field of medicine by yielding knowledge that could allow doctors to prevent miscarriages and grow synthetic organ replacements, Hanna’s claims of ethical permissibility are almost certainly premature.

With time limits on the lab growth of embryos being lifted and recent advances in artificial wombs, the theoretical possibility that “synthetic” human embryos could be created and grown in laboratories to any stage of development isn’t only possible. It’s likely.

Dare I say…imminent?

Is this research ethical? The discussion hasn’t even begun. Here is a list of questions to get us started.

What does “synthetic” mean, anyway?

Hanna claims that his mice embryos are not “real” embryos because they haven’t yet developed into live mice when transplanted into the wombs of female mice. The synthetic embryos reportedly resemble real embryos about 95%, with “some defects in organs and change in size.”

Before testing with human cells, it is vital to determine what exactly is meant by the word “synthetic.” If the cells have human DNA and develop into a human embryo, it seems that a more precise way to describe the resulting creatures would be lab-synthesized embryos. The difference in terminology is significant because while one term suggests these are not real embryos, the other specifies that it is merely their origins that are distinct.

Other papers have avoided using the term embryo altogether, calling these lifeforms “blastoids” in an attempt to distinguish them from “real” embryos. (It’s worth noting that experimentation with human “blastoids” has already begun; it just hasn’t progressed to the embryonic stage of development.)

Would Synthetic Embryos Possess Human Dignity?

What would this creature be that resembles a human embryo 95%, with a brain and beating heart and some defective organs? Could a living embryo with human DNA be anything other than a human being?

Is this a case of a “rose by any other name,” or have researchers created a genuinely unique form of life, hitherto unimaginable to us?

Is it a human being? A sub-species?

If we apply Hanna’s logic regarding mouse embryos, the argument would go something like this: “They are not real human embryos because they have not developed into human beings yet.” And while we can recognize in this statement the logic employed by abortion advocates, it is also absurd to tell a woman having a miscarriage that the creature she is losing is not human because it is “not capable of developing into one.”

We have a serious problem when the people creating the lifeform are the ones naming it and, in doing so, bestowing or withholding dignity.

Researchers like Hanna have a pressing interest to define lab-synthesized embryos as “synthetic” or “blastoids” to characterize them as other, as not human, so as to bypass the ethical fallout they face in experimentation with embryos created using eggs and sperm. In some literature, they describe synthetic embryos as “embryo models” for just this purpose. But when a “model” is made of living human cells, how can we call that anything but experimentation on nascent human life?

Public debates over research on synthetic human embryos are likely to fall along the same lines as other debates about personhood which tend to tie it to abilities like intelligence, sentience, communication, etc. How do we have that conversation about a novel being that hasn’t ever fully developed…yet?

For those who argue that dignity is innate, belonging to creatures of a rational kind, this research ought to give us serious pause. How can we know whether these are creatures of a rational kind if one has yet to be brought into being?

Ought we to bring such creatures into being?

Should we reproduce asexually?

I mean, no. Full Stop. This shouldn’t even be a question.

But, because we live in a free, pluralist society in which someone will inevitably wish to do so anyway, the argument must be made.

Whatever a “blastoid” or synthesized human being is, whatever its origins, and whatever its capacities, it will be a creature comprised of human DNA. Regardless of potential functioning, it is comprised of the same code we are. We ought to proceed as though these creatures have dignity equivalent to our own because we cannot know whether their capacities will make them “creatures of a rational kind” until after they are brought into being. Furthermore, there are many creatures of a rational kind that do not themselves posses the capacity to reason.

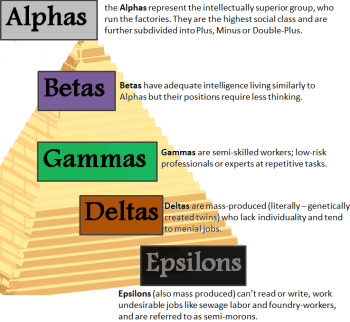

How will we know that we have created something truly other and not merely engineered for ourselves a sub-class of human beings akin to Huxley’s Epsilons, genetically engineered as medical research subjects rather than menial laborers?

What constitutes justice for lab-synthesized human beings?

Assuming that research progresses to the point where it produces beings relatively similar to ourselves, what sort of treatment might these beings merit? It should be quite obvious that raising them as a captive research class is out of the question. But what are some ethical considerations of producing human beings in this manner?

We already know that donor conceived people often experience significant distress related to the idea of being “laboratory experiments.” How can we possibly justify creating beings out of our genetic material merely for the purposes of experimentation?

It is not that these people would be “better off not existing,” as so many argue to justify abortions, but rather that to intentionally create persons in this way does not measure up to the kind of dignity we ought, by default, to afford them.

As more states move to lift donor anonymity, exacerbating the “great sperm shortage,” some will inevitably look to synthesizing embryos as a means to avoid the need for donors (and the complications that come with them), and to the artificial uterus as a means to sidestep the need for surrogates. We already create children in a lab via IVF. We already select embryos based on their genetic potential.

How long is it, really, before we see the laboratory as the safe and effective means of reproduction?

And while such processes undoubtedly violate the rights of children “to be conceived, carried in the womb, brought into the world and brought up in marriage,” as Donum Vitae articulates, conversations about reproductive rights are rarely, if ever, framed in terms of what constitutes the good of the children.

Of course, researchers, the fertility industry, and the media are unlikely to refer to these research subjects as “children” for a long while.

My guess? The dehumanizing rhetoric will continue so as to allow research to progress — right up until the point they’re ready to start charging for them.

Books: Mama Prays | Reclaiming Motherhood from a Culture Gone Mad

Connect: Twitter | www.SNStephenson.com

Podcast: Brave New Us